“To make a film is easy; to make a good film is war. To make a very good film is a miracle.” Alejandro G. Inarrito

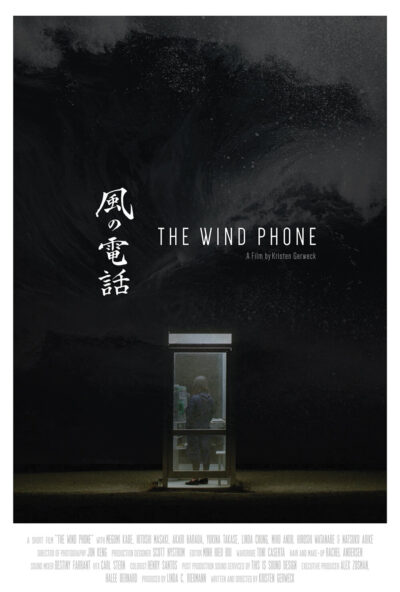

Kristen Gerweck Diaz (formerly Kristen Gerweck) is a versatile filmmaker and former lawyer. After obtaining her J.D. from UCLA Law School, she transitioned into film, theater, and television studies. Kristen's debut short film, EAST RAMADI, received critical acclaim, screening at Cannes Emerging Filmmaker Showcase and securing distribution in European theaters. Her second film, THE WIND PHONE, earned numerous awards and an Academy Awards qualification. Kristen also penned a science-fiction thriller, THE NATURE OF APRIL, for ANVL Entertainment and is currently adapting a climate change-themed novel. Her filmography includes EAST RAMADI (2016), THE WIND PHONE (2019), and executive producing OUT OF TUNE (2022).

Kristen, from East Ramadi, your first short film as writer and director as well -chosen as one of five films to premiere at the 2016 Cannes Emerging Filmmaker Showcase-, to The Wind Phone -which has received 43 awards- how do you picture yourself as a filmmaker?

I am not a filmmaker who is married to any particular genre or style of story-telling. In fact, I love exploring different genres in my work. My only rule as a writer and filmmaker: to chase stories that touch something in my own soul. When that connection is there, I find that my subject matter informs me of how to creatively approach the story. I listen to my characters.

Did you happen to know whose idea was to place the phone booth on the outskirts of Otsuchi?

Itaru Sasaki, an Otsuchi resident, constructed the booth a year before the tsunami devastated the small town. In a time of deep grieving, Sasaki used the phone to stay connected to his beloved cousin who had passed away. Sasaki states on an episode of This American Life, “because my thoughts couldn’t be relayed over a regular phone line, I wanted them to be carried on wind”. In the aftermath of “3-11”, Sasaki opened his phone booth to the public, realizing it could help others in the grieving process. Since then, the phone booth has become a destination for people across Japan who have lost loved ones under various circumstances and it has welcomed more than 10,000 visitors to date. The concept of the wind phone has now also spread to other cultures, with wind phones being installed in countries around the world. Sasaki’s story is proof that one act of hope can truly change the world.

What drove you to bring this subject matter to the screen? Do you actually know any survivors from the 2011 earthquake and tsunami?

I initially discovered the true story behind THE WIND PHONE on an episode of This American Life. I was deeply affected by Itaru Sasaki’s beautiful act – creating the wind phone, and then sharing this sacred grieving space with the survivors of 3-11. But it was not until I suffered the unexpected loss of my own grandmother, that I wrote THE WIND PHONE. I myself was longing for a wind phone – as there were so many things I wanted to say to her, but never got the chance. After this loss, the wind phone spoke to me on a whole new level. And while I did not personally know any of the survivors, I found that casting native Japanese actors, with personal connections to the tragedy, brought the film a powerful emotional authenticity.